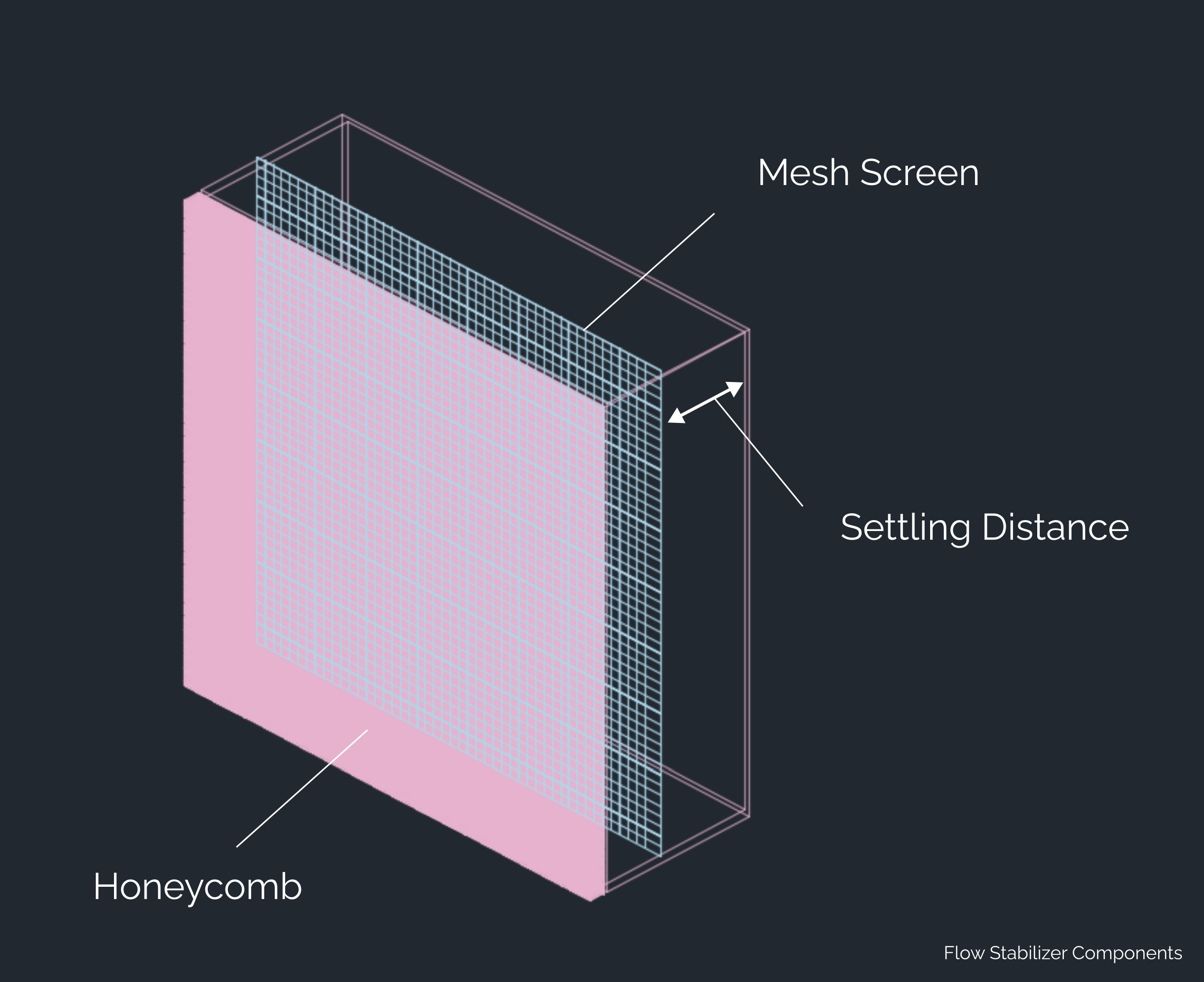

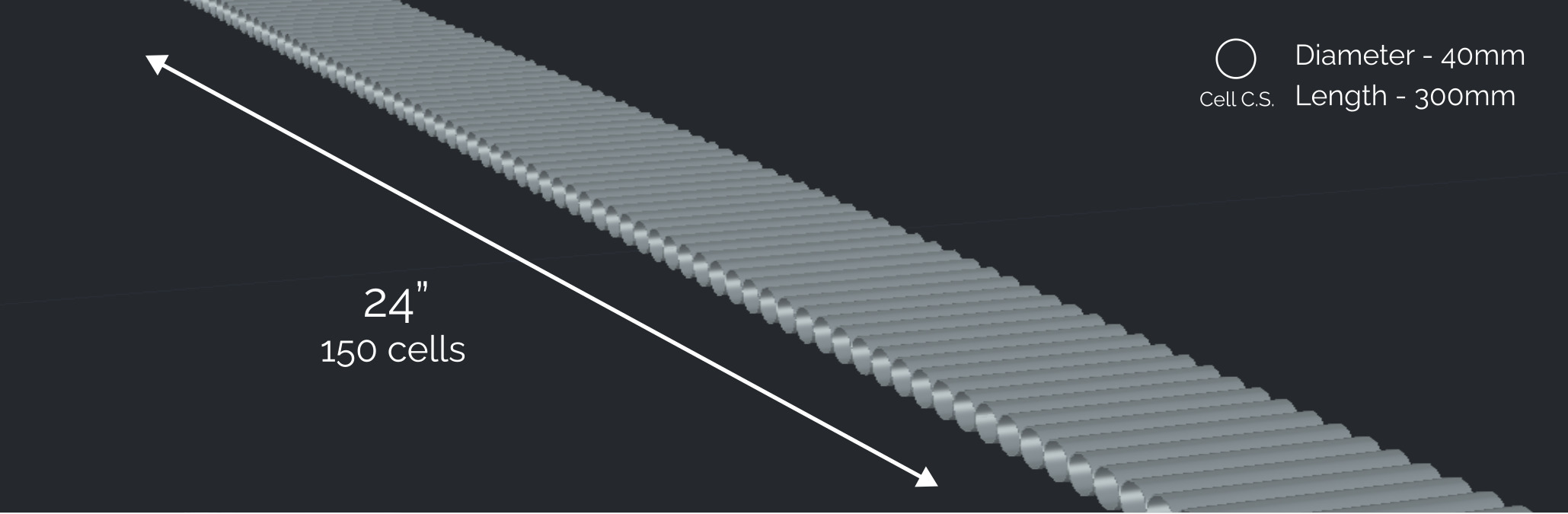

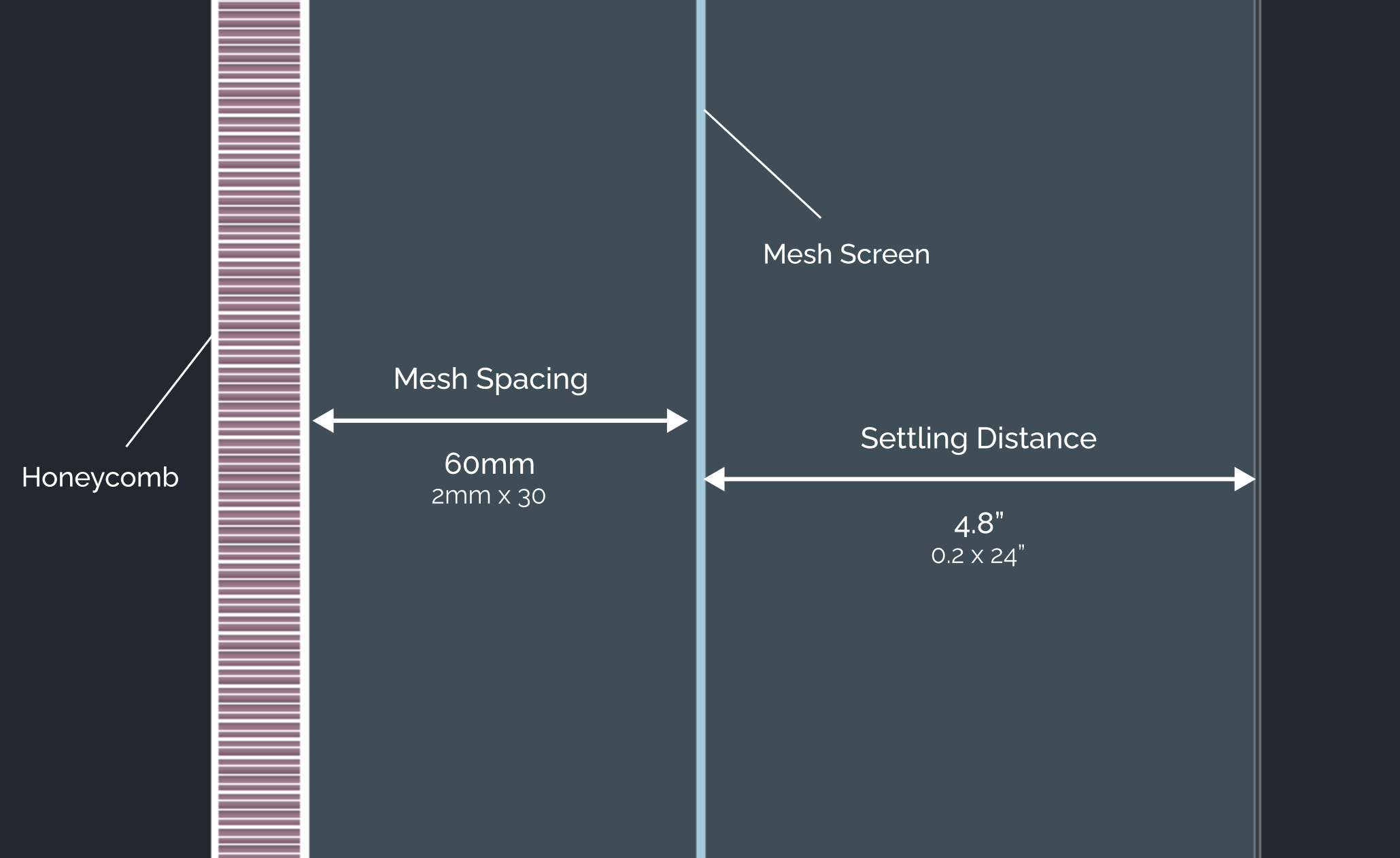

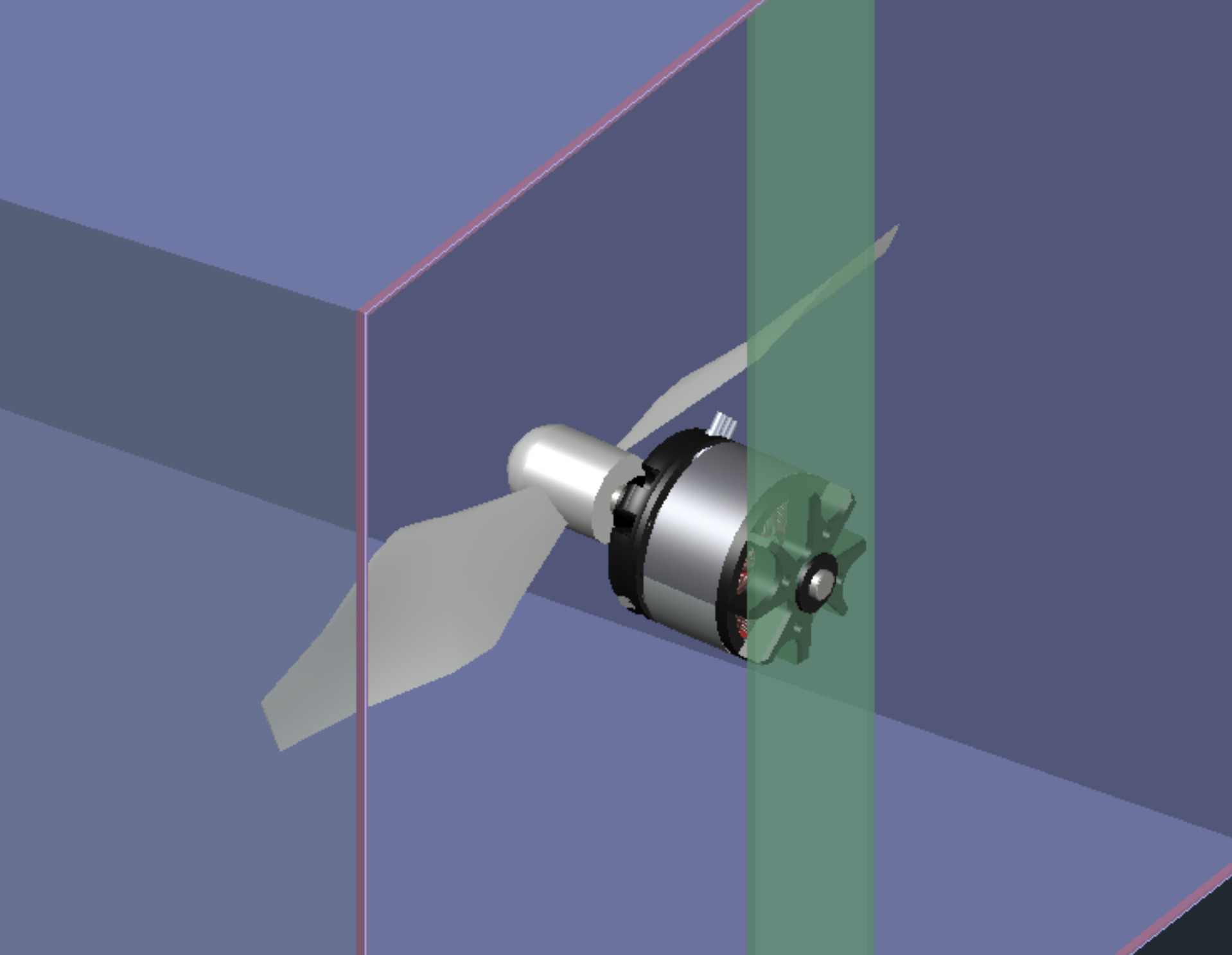

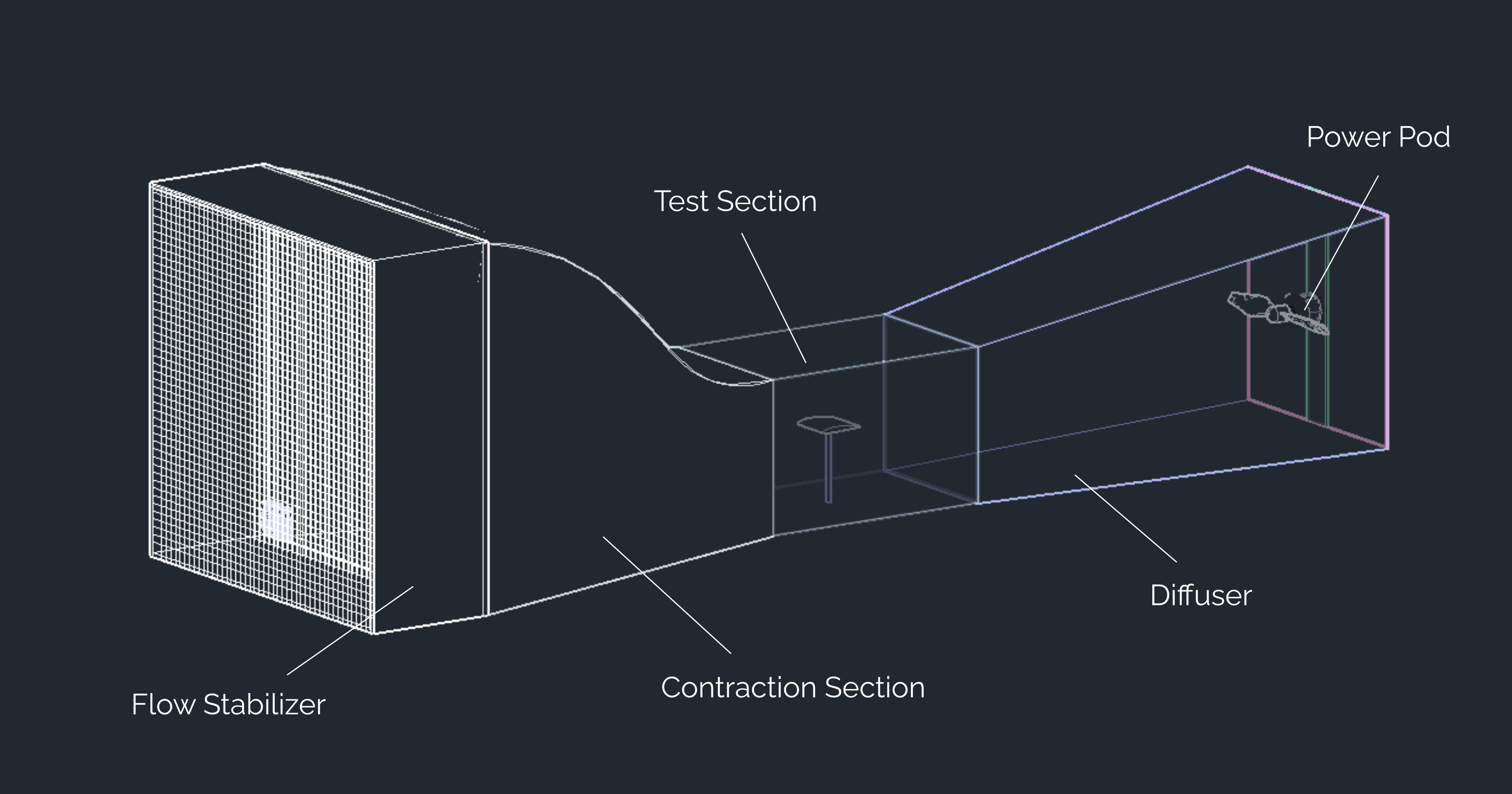

Wind Tunnel Components

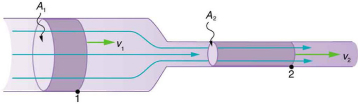

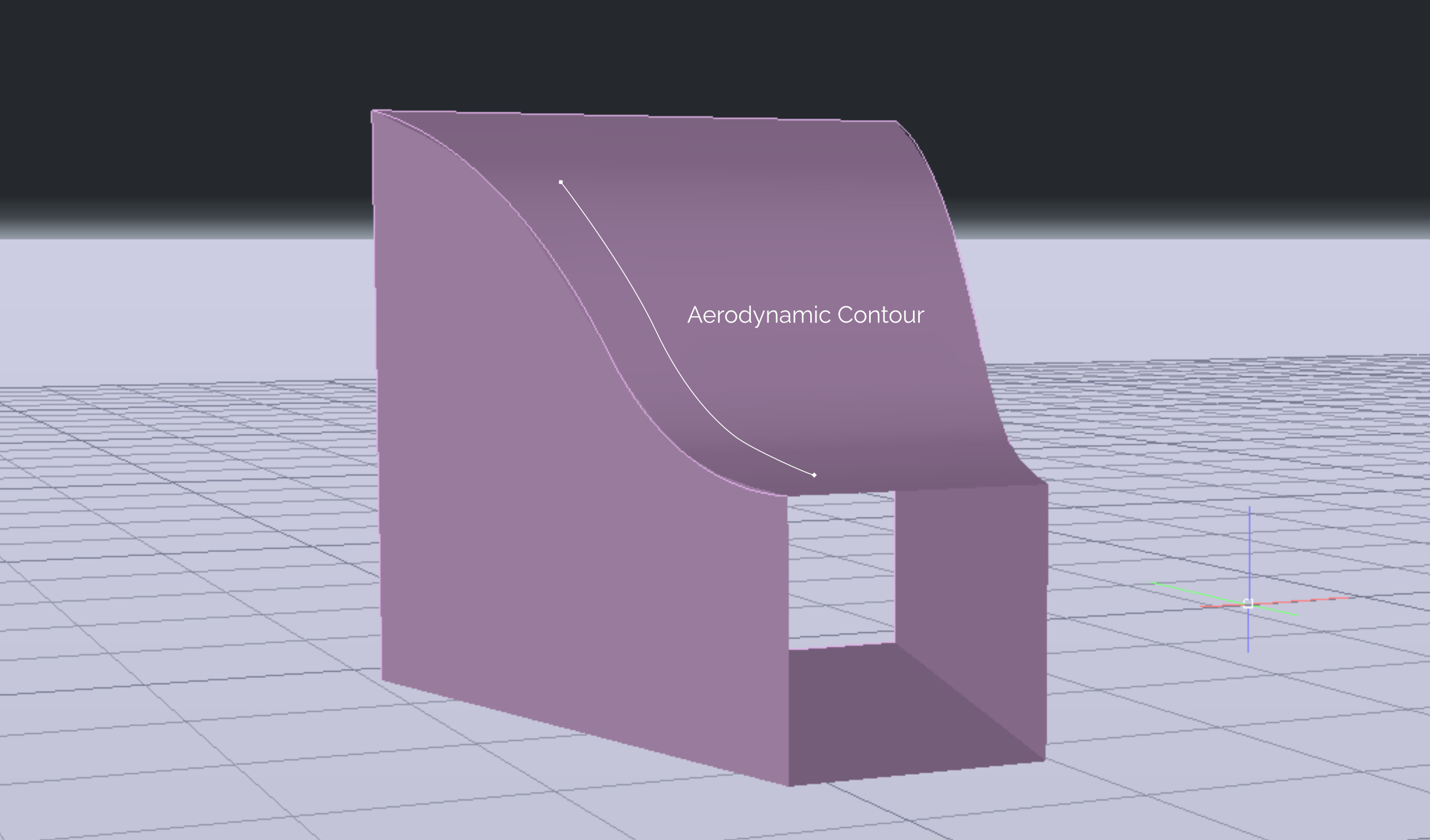

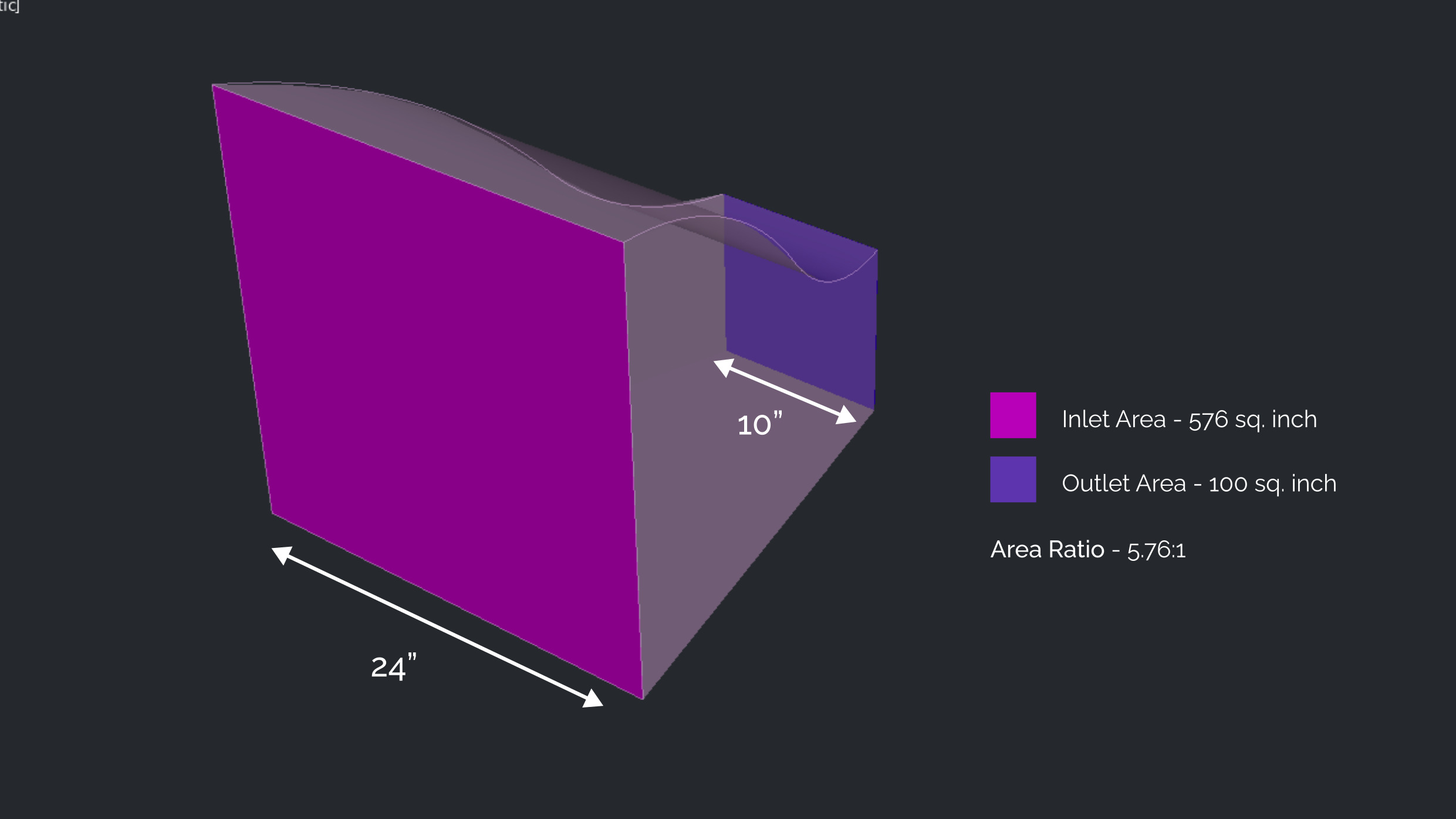

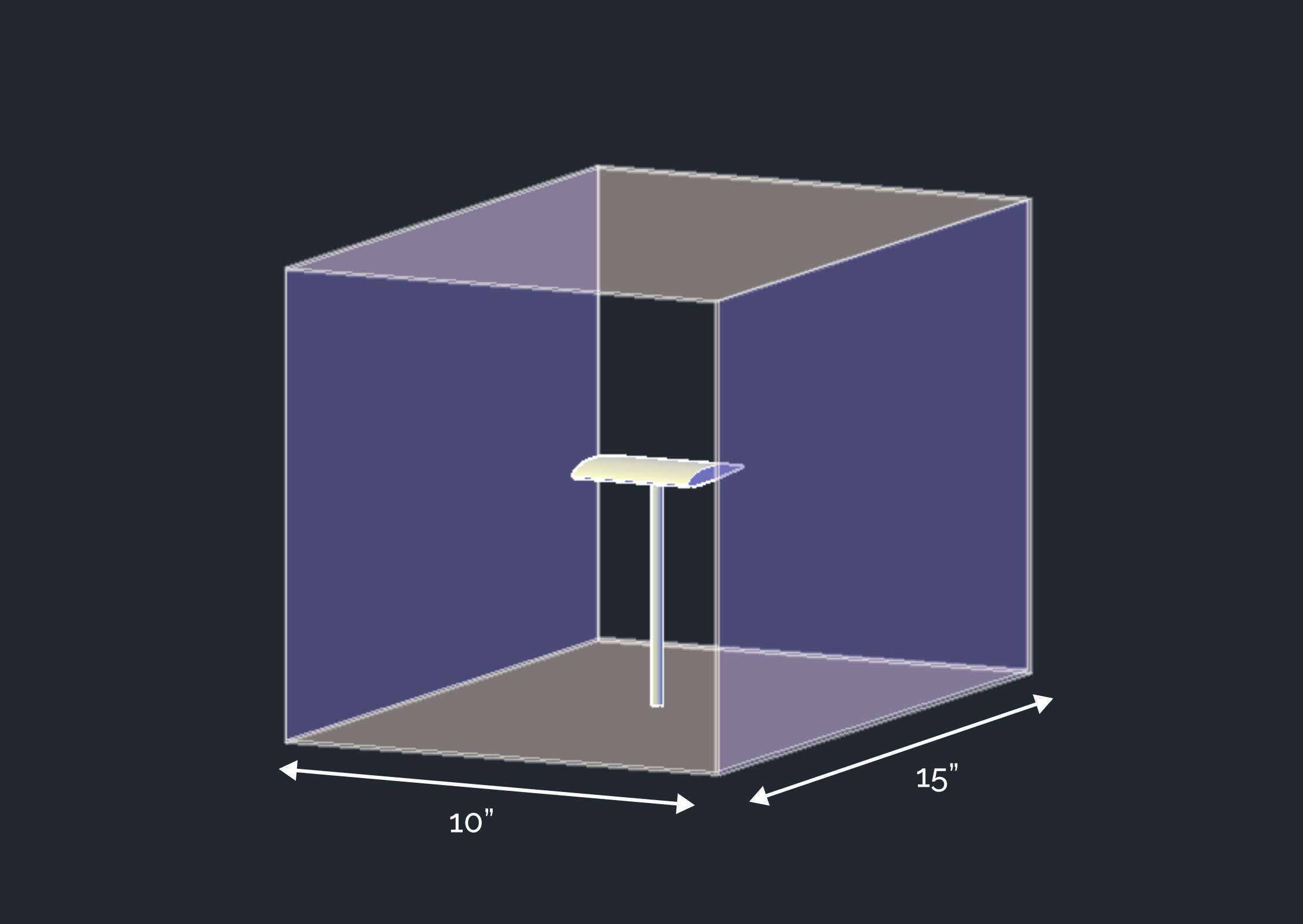

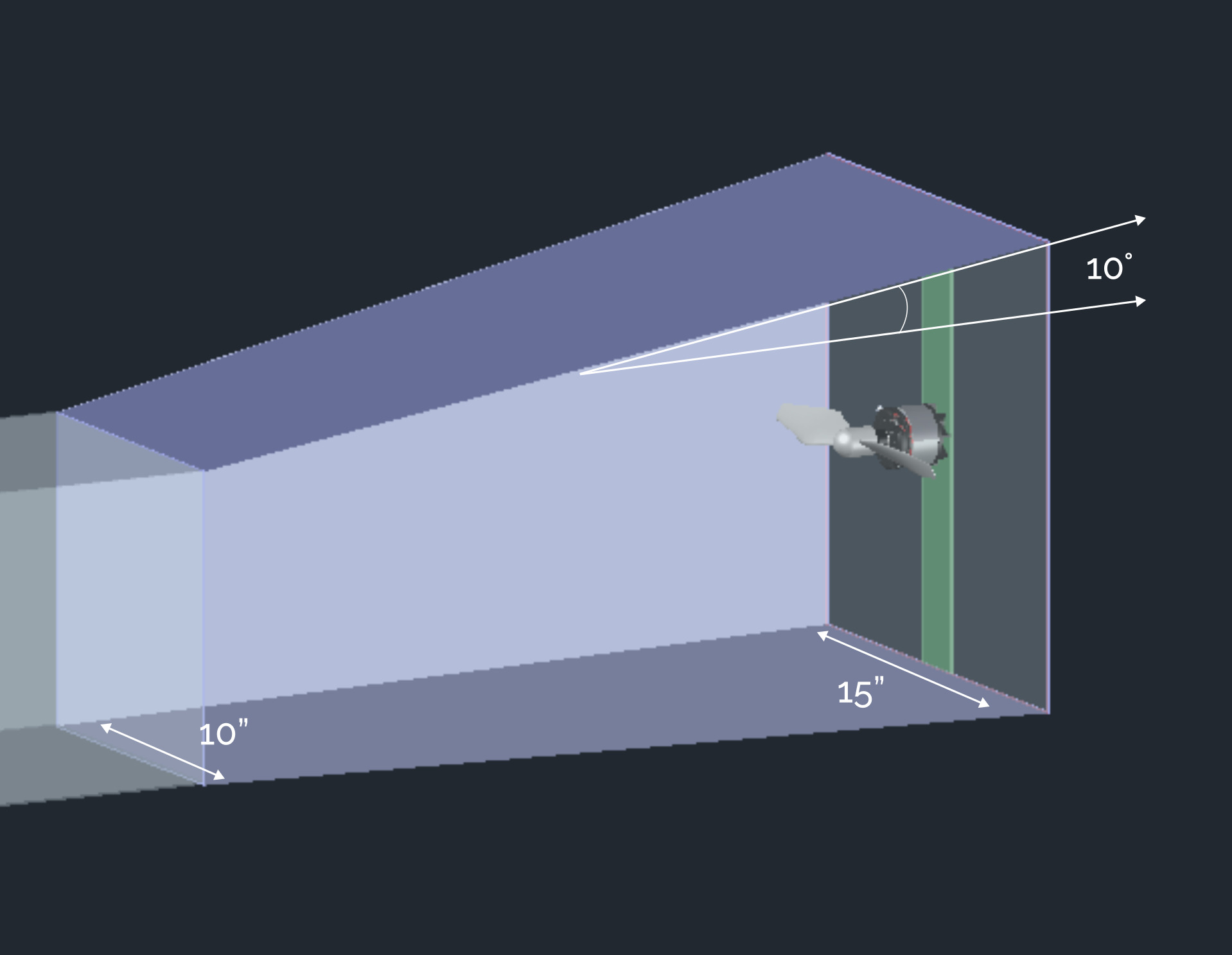

The purpose of windtunnels is to produce feasible circumstances for aerodynamic testing that are centered around the goal of producing reproducible conditions of turbulence-free airflow. Getting the cleanest possible airflow into the test section is the primary goal.

This innocent-seeming task poses immense obstacles with restrictions in each component of the apparatus. Furthermore, besides these intricate technical restrictions, there

are many more non-technical.

This wind tunnel takes on the following general restrictions:

- Build effort

- Finances

- Accessibility of material